Man who fled North Korea for America returns to feed starving citizens: 'God called me'

As a teenager, Joon Bai walked six weeks without food in the freezing winter to reach South Korea

American born in North Korea reveals what happens inside of military dictatorship

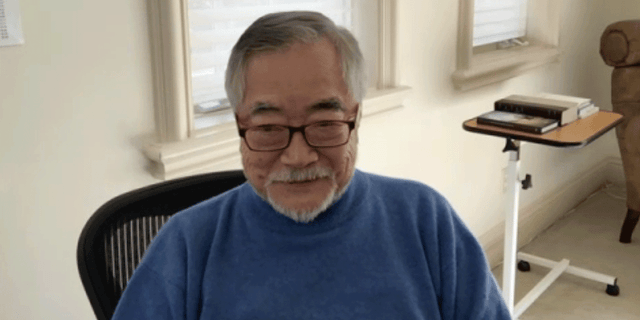

85-year-old Joon Bai fled North Korea as a teenager before becoming a successful businessman in the United States.

A man who fled North Korea as a teenager revealed that his Christian faith and his success in America led him back to his home country to feed famine-stricken people, saving countless lives.

Fox News Digital spoke with 85-year-old Joon Bai, a humanitarian, author and award-winning movie producer who, with support from his wife, Kyuhee, returned many times to his birthplace for philanthropic support to farmers and orphans.

"North Koreans, they don't know religion. They don't know Jesus Christ, Muhammad or Buddha. Teaching them that there is life afterward, there's an eternity. I'm seeding religion into their minds. That's my greatest achievement," Bai said.

In his new memoir, "Promises: The Life and Love of an American Born in North Korea," Bai recounts his extraordinary life and stories of courage, overcoming adversity and finding hope.

Joon Bai is a successful entrepreneur and humanitarian. With the support from the love of his life, his wife, Kyuhee, he returned many times to his birthplace, North Korea, to assist farmers, orphans and numerous others with philanthropic support. (Fox News Digital )

The book, he hopes, will speak for the 23 million North Koreans who do not have a voice.

"We know very little about North Korea. We really don't know anything. The only thing we know is what the media tells us about missiles and Kim Jong Un."

But, what about the rest of those people? Who are they? What do they believe?

North Korea has closed its fences, so they don't know what's outside, Bai noted. The same applies to the inside of the Korean Demilitarized Zone (DMZ), where people only hypothesize about what plants and animals thrive there.

Travelers from other countries are only allowed to places in North Korea under a guide. Bai said they are told what they are allowed to see, don't talk to people on the street and are not allowed to take pictures unless approved beforehand.

Bai has visited North Korea numerous times over the last two decades, visiting the most desolate places to sit and talk with the farmers and the orphans. They don't have neighbors with BMWs or Mercedes-Benz vehicles. Instead, they live off rations, only what the government provides them to eat.

"That village, those farmers, to them, there's no such thing as murder or killings. I would never say that here it happens all the time in the back streets of Oakland, Brooklyn, or Detroit, Michigan."

Promises is a unique and intimate look inside North Korea and the life of Joon Bai, offering lessons he has learned about courage, challenges, and hope. (Trans Western Pictures LLC (Jenkins))

During his North Korean travels, he wrote and co-produced the award-winning movie, "The Other Side of the Mountain," a feature film that was the first collaboration between an American and the North Korean government. The movie details a love story with a message close to Koreans on both sides of the border, unification.

During the movie's production, Bai didn't pay a dime to the actors because there's no such thing as pay in North Korea.

"In the U.S., you make a movie, 20 or 30% of the budget goes to the top actors. Tom Cruise is a big part of the budget for that movie. In North Korea, there is no such thing," Bai said.

In North Korea, citizens must have a permit if more than five or six people get together. Bai said this is likely to prevent them from starting a revolution.

From his early childhood years in what is now North Korea, Bai lived through the devastation of World War II and the Korean War. Bai's family eventually left their hometown in North Korea — near the Chinese border — and made the journey to Seoul, South Korea, on foot.

The Korean War had a devastating toll on Koreans. But, should you ask, the people on both sides of the DMZ would tell you there are worse things than the cruelty of the fellow man.

"Winter in Korea was the worst," Bai said.

The Northern tip of North Korea has the same climate as Siberia. Bai said he had to keep moving or freeze to death to survive. He walked for six weeks without anything to eat.

After living in South Korea, Bai came to the United States as an exchange student. After earning his engineering degree, he embarked on a successful career in business, working in natural gas among Fortune 500 CEOs. Eventually, Bai opened his own factory in rural Pennsylvania. The factory employed 400 people and everybody in town knew somebody who worked for Bai.

"It was my way of paying back what I was given. Wonderful country," Bai said.

Looking back on his town in Missouri and Pennsylvania, Bai said he never felt discriminated against. He also said he is "deeply grateful to his new country, America, for embracing him and giving him every opportunity."

"I hate to say I think we're walking backward today," Bai said. "So, I hope the people read my book and say, well, this kid came from Korea and he did good things and he loved his wife to the end. Maybe we should learn something from him. Maybe I should be a little nicer to my wife and kids tonight."

"Those were the days you could smoke in the airplane," he laughed.

In this undated photo provided on July 23, 2020 by the North Korean government, North Korean leader Kim Jong Un, center, visits a new chicken farm being built in Hwangju County, North Korea. (Korean Central News Agency/Korea News Service via AP, File)

Growing up, Bai saw how the world was recovering from the aftermath of Adolf Hitler's rule in Germany. Today, people speak similarly of Vladimir Putin and North Korea.

"Today, we have these people living in North Korea and we think all 23 million are evil people. They are not, only a handful of leaders," Bai said. "Sometimes, when you don't have freedom, you are truly innocent."

Bai says he does not believe North Korea can strike the United States with ICBM missiles. He thinks it is all a defensive measure. He also does not believe North Korea could successfully invade South Korea.

"They keep shooting one or two missiles every year just to tell the world, 'I'm a little rat cornered. I can bite you one time before I die,'" Bai said.

In January 1997, it was raining so hard in San Francisco, California, that Bai could barely see out his car windshield. He was listening to the radio when he heard over 100,000 children had died of starvation in North Korea. That night, he came home and told his wife.

"We just couldn't eat. We couldn't sleep," Bai said.

In this photo provided by the North Korean government, a huge North Korean flag is displayed during a celebration of the nation’s 73rd anniversary at Kim Il Sung Square in Pyongyang, North Korea, early Thursday, Sept. 9, 2021. (Korean Central News Agency/Korea News Service via AP)

His wife would often ask him how there are so many orphans in North Korea. He told her their parents had died of starvation. The kids often live longer than their parents, whether a few more weeks or days.

Babies drink their mother's milk until the parent dies. The government then picks up the children and brings them to the orphanages.

Bai said young kids die in the orphanages for two reasons: Diarrhea and water. They don't have purification facilities and they cannot digest the food they are given. These facilities often do not have milk, so they provide the children with hard food like corn.

"You feed that to a one-year-old baby, she dies," Bai said.

During a Korean Winter, the ground is firm and the orphanages only have a few young female volunteer nurses. So, they throw the bodies next to the barns, stacking them up into a frozen pile. When spring comes and the snow melts, they dig into the earth and bury those children.

The malnutrition has caused North Koreans to be up to three inches shorter than South Koreans on average and have a 20-point difference in terms of IQ.

"I'm not an AP press writer or United Press International. I'm just an ordinary guy who happened to be born in North Korea and loved the people, and became wealthy, got resources. So, I went back and fed them," Bai said.

A friend told Bai to send a palette of food to the North Korean government, so he did. The leaders of North Korea wrote back to him, thanking him, which opened the door for him to return to his country.

Bai spent close to one million dollars of his savings and began procuring goods like corn, potatoes, hairclips, and washing machines in China for five or six years. He then took those goods and brought them over to North Korea. He did this until 2019, when travel to North Korea was closed under the Trump administration.

Much of the food went to young kids going through the education system in North Korea.

People watch a TV showing a file image of North Korea's missile launch during a news program at the Seoul Railway Station in Seoul, South Korea, Saturday, May 7, 2022. (AP Photo/Ahn Young-joon)

"These kids, they break the bread in half and bring the rest home to their parents," he said. "So, when I saw that, I thought, giving bread and rice and all that is not enough. I have to teach them how to grow the farm products."

That is when Bai started what he described as his "agricultural revolution."

Bai went to China and hired farm experts who helped him teach the poor people of North Korea seeding, growing and mulching over the course of several years.

According to Bai, when he left North Korea, they produced 1,000 times more rice per season than in previous years. He thought that nobody would go hungry if he could do that for the rest of the country. He succeeded.

While staying in a hotel room in the country, Bai dropped to the ground and cried. People he worked with rushed over to ask if he was OK. One person said that was when God came to his heart.

"It is in that process of being able and willing to help other people, the faith grew. And I think God called me. It just happened very naturally," Bai said. "My mind was full of passion to help those kids. Every second, my mind was focused on that."

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

It was an effort, Bai notes, that was inspired by his wife and the Christian faith his mother instilled in him. The book is dedicated to those two women, two shining pillars in his life.

He visits his wife's grave every week, sitting among beautiful trees, fresh air and rolling hills. His mother's ashes reside with him at his home in Pleasanton, California.

After reading his story, Bai hopes that others will be inspired to make a change and spread love throughout the world.

"Today, I believe whatever I did is God's will. He chose me to do certain things," he said. "That's really what it's all about. God's faith in me gave me the courage to love other people. So, whatever is left of my life, I'm smiling."

FOX NEWS

No comments:

Post a Comment