The Beloved Community: Martin Luther King Jr.’s Prescription for a Healthy Society

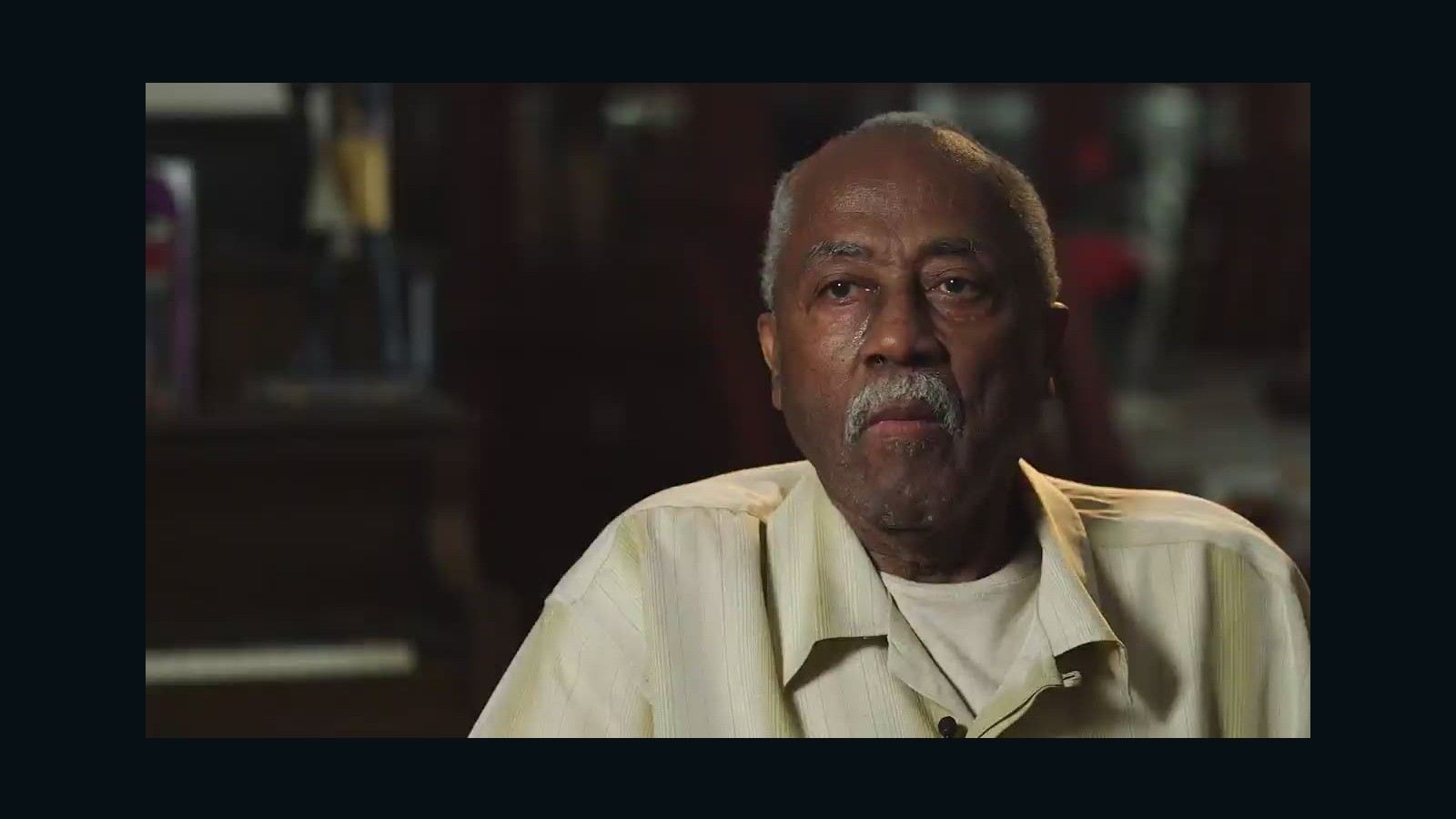

Image courtesy of Vivien Feyer*

Dr. Martin Luther King popularized the notion of the “Beloved Community.” King envisioned the Beloved Community as a society based on justice, equal opportunity, and love of one’s fellow human beings.

As explained by The King Center, the memorial institution founded by Coretta Scott King to further the goals of Martin Luther King:

Dr. King’s Beloved Community is a global vision in which all people can share in the wealth of the earth. In the Beloved Community, poverty, hunger and homelessness will not be tolerated because international standards of human decency will not allow it. Racism and all forms of discrimination, bigotry and prejudice will be replaced by an all-inclusive spirit of sisterhood and brotherhood.

How is King’s Beloved Community a prescription for a healthy society?

Fundamental to the concept of the Beloved Community is inclusiveness, both economic and social. The notion that all can share in earth’s bounty describes a society in which the social product is shared far more equally than it is in today’s world. The Beloved Community also describes a society in which all are embraced and none discriminated against.

Economic and social justice are the twin pillars supporting the Beloved Community. These twin pillars are also necessary for a healthy society. What would be the health impacts of living in such a society?

Quite a lot is now known about health and social status. When I was in medical school in the 1970s, we believed that it was the CEO at the top of the hierarchy who would be the first to succumb to a heart attack due to the undue stresses of his high position.

Sir Michael Marmot, in the famous Whitehall Studies, showed that actually the exact opposite is true. The lower one is on the social hierarchy, the lower one’s life expectancy, with an incremental improvement each step up. We humans are exquisitely sensitive to our class standing. Our stress hormones reflect this. Those of us lowest on the social pyramid have the highest stress hormone levels. This seems to be how we are wired. The same is true in baboons.

It turns out that social status is the most powerful determinant of health for a wide range of outcomes including life expectancy, as well as illness and death from cardiovascular, pulmonary, psychiatric, and rheumatologic diseases and some cancers. It’s not only where we find ourselves on the social pyramid that matters, it also matters how that pyramid is shaped. In countries with relatively gentler hierarchies and more income equality, health outcomes and social well-being are generally quite good.

In highly unequal countries, like the United States, health outcome and social well-being suffer. We don’t live as long as our peers in more equal countries, nor do our infants or children. We’re fatter, more of our teens get pregnant, we incarcerate more of our citizens, our children score worse on math and science tests, we trust one another less, and we kill one another more often. We even recycle less often. Greater inequality of income leads to a generalized societal dysfunction. We correctly perceive that we are not all in the same boat, and we are more likely to view the world as a Hobbesian struggle for individual survival and advantage.

The King Center addresses one of the key public health challenges of our time by emphasizing a fairer sharing of the social product and an elimination of poverty and homelessness. Since social causes determine how long we will live and whether or not we will get ill, our prevention strategies must advance health-promoting changes in social policy.

The science suggests that policies that lessen income inequality, like raising the minimum wage and increasing taxes on corporations and the wealthiest among us, are likely to lead to significant population health benefits.

Dr. Martin Luther King popularized the notion of the “Beloved Community.” King envisioned the Beloved Community as a society based on justice, equal opportunity, and love of one’s fellow human beings.

As explained by The King Center, the memorial institution founded by Coretta Scott King to further the goals of Martin Luther King:

Dr. King’s Beloved Community is a global vision in which all people can share in the wealth of the earth. In the Beloved Community, poverty, hunger and homelessness will not be tolerated because international standards of human decency will not allow it. Racism and all forms of discrimination, bigotry and prejudice will be replaced by an all-inclusive spirit of sisterhood and brotherhood.

How is King’s Beloved Community a prescription for a healthy society?

Fundamental to the concept of the Beloved Community is inclusiveness, both economic and social. The notion that all can share in earth’s bounty describes a society in which the social product is shared far more equally than it is in today’s world. The Beloved Community also describes a society in which all are embraced and none discriminated against.

Economic and social justice are the twin pillars supporting the Beloved Community. These twin pillars are also necessary for a healthy society. What would be the health impacts of living in such a society?

Quite a lot is now known about health and social status. When I was in medical school in the 1970s, we believed that it was the CEO at the top of the hierarchy who would be the first to succumb to a heart attack due to the undue stresses of his high position.

Sir Michael Marmot, in the famous Whitehall Studies, showed that actually the exact opposite is true. The lower one is on the social hierarchy, the lower one’s life expectancy, with an incremental improvement each step up. We humans are exquisitely sensitive to our class standing. Our stress hormones reflect this. Those of us lowest on the social pyramid have the highest stress hormone levels. This seems to be how we are wired. The same is true in baboons.

It turns out that social status is the most powerful determinant of health for a wide range of outcomes including life expectancy, as well as illness and death from cardiovascular, pulmonary, psychiatric, and rheumatologic diseases and some cancers. It’s not only where we find ourselves on the social pyramid that matters, it also matters how that pyramid is shaped. In countries with relatively gentler hierarchies and more income equality, health outcomes and social well-being are generally quite good.

In highly unequal countries, like the United States, health outcome and social well-being suffer. We don’t live as long as our peers in more equal countries, nor do our infants or children. We’re fatter, more of our teens get pregnant, we incarcerate more of our citizens, our children score worse on math and science tests, we trust one another less, and we kill one another more often. We even recycle less often. Greater inequality of income leads to a generalized societal dysfunction. We correctly perceive that we are not all in the same boat, and we are more likely to view the world as a Hobbesian struggle for individual survival and advantage.

The King Center addresses one of the key public health challenges of our time by emphasizing a fairer sharing of the social product and an elimination of poverty and homelessness. Since social causes determine how long we will live and whether or not we will get ill, our prevention strategies must advance health-promoting changes in social policy.

The science suggests that policies that lessen income inequality, like raising the minimum wage and increasing taxes on corporations and the wealthiest among us, are likely to lead to significant population health benefits.

Let’s focus for a moment on high blood pressure, a common ailment in African Americans. West Africans of similar heredity do not suffer from high levels of hypertension. What’s the explanation for such high levels in African Americans?

Our brains orchestrate an exquisite symphony of neuro-hormonal signals, resulting in the appropriate blood pressure for the level of threat or challenge we face at any given time. When the brain perceives the threat going up, blood pressure goes up too. The world can be a challenging place for a small biped without sharp teeth or claws. It’s good to be prepared for fight or flight should the situation call for either. The world is even more threatening if your racial group is discriminated against.

The appropriate physiologic response to perceived threat is vigilance and preparedness to run or to fight. Given that racism permeates our social environment, the brain of a person suffering racial discrimination sees hypervigilance as a necessity in order to be able to cope with any challenges that may arise. I imagine that tragedies like the murders of Trayvon Martin and Oscar Grant must reinforce the feeling that hypervigilance is necessary.

The hypervigilant state comes with a price. Chronically elevated blood pressure has a weathering affect on the heart and blood vessels. Being ready to run or to fight all of the time takes it’s toll. Heart disease, strokes, kidney failure and premature death are the results. A normal physiologic response (blood pressure rise) to an unhealthy social environment can lead to illness and death. You would think that one focus of intervention would be on improving the social environment and reducing racism. This is not the case.

The physician who treats the hypertensive patient unwittingly performs the social function of normalizing the status quo by ignoring the root cause of the high blood pressure and focusing exclusively on the patient’s response to drug therapy. Knowledge of the social causation has been largely kept from the physician who was taught in medical school that this is “essential hypertension” as opposed to the very rare instances of hypertension caused by endocrine secreting tumors. The terrible irony is that the patient’s brain felt it “essential” to maintain the blood pressure at elevated levels to deal with the chronic stress that is racism.

The medical world’s response to this phenomenon of stress-induced hypertension, in this case due to racism, is to treat each individual patient with multiple medicines. Controlling blood pressure with medications is an enormous challenge. The brain controls blood pressure. When the brain senses that the social environment is threatening, the blood pressure goes up. The doctor prescribes medicines aimed at interrupting the various neuro-hormonal messages that the brain sends to the heart, blood vessels and kidneys to maintain this elevated stress-induced blood pressure.

The doctor typically prescribes a beta-blocker to counteract the effects of the adrenaline system, thereby decreasing the rate and strength of the heart’s contraction, and lowering the blood pressure. The brain, still aware that the social environment is threatening, counters by having the kidneys hold on to more fluid — driving the blood pressure back up.

The doctor responds with a diuretic. The brain, not to be outdone by the doctor, increases the hormone angiotensin, leading to blood vessel constriction and again driving up blood pressure. The doctor has a medication for this too. She prescribes an ACE inhibitor and perhaps nitrates. At this point the patient’s blood pressure may be controlled, as long as the patient can tolerate the expense, the inconvenience and the side effects.

But unless the structures that perpetuate racism are removed, the next generation of African Americans will meet the same fate and they, too, will need to be treated for high blood pressure. This may be good for “fee for service medicine” and for the pharmaceutical industry, but it will never lead to a healthy society.

Dr. King devoted his life to creating the Beloved Community. By doing so he showed us the path to a society that maximizes empathy, compassion and love and also leads to health and well being. We can realize Dr. King’s dream, but to get there America will need to deal successfully with unresolved issues of class and race. Specifically, we need to share the social product more equally and to provide a livable income for all while at the same time removing any and all structures that promote or allow racism or any other form of discrimination.

In Dr. Kings words:

“The end is reconciliation; the end is redemption; the end is the creation of the Beloved Community. It is this type of spirit and this type of love that can transform opponents into friends. It is this type of understanding goodwill that will transform the deep gloom of the old age into the exuberant gladness of the new age. It is this love which will bring about miracles in the hearts of men.”

Images courtesy of Vivien Feyer, gifts of the Society for the Support of Chemical Weapons Victims, Tehran, Iran

Follow Jeff Ritterman, MD on Twitter: www.twitter.com/@JeffRitterman

Do you have information you want to share with the Huffington Post? Here’s how.

Jeff Ritterman, MD Vice President of the Board of Directors, San Francisco Bay Area chapter of Physicians for Social Responsibility