“To Be Young, Gifted and Black” is a song by Nina Simone with lyrics by Weldon Irvine.

Simone had introduced the song on August 17, 1969, to a crowd of 50,000 at the Harlem Cultural Festival.

As it would later turnout Simone could have easily had Steve Biko in mind when she delivered the unforgettable classic.

Of course, the real reason for the title of the song comes from Lorraine Hansberry’s autobiographical play, To Be Young, Gifted and Black, in which Simone had written in memory of her late friend Lorraine Hansberry, who is also author of the play A Raisin in the Sun, who had died in 1965 aged 34.

Some in paying tribute to Biko would incur the title ‘Young, Gifted and Black” on Biko as it is fitting to confer such honor on the iconic Steve Biko, “The Godfather of Black Consciousness in South Africa (Azania)”.

Born December 18, 1946 Bantu Stephen Biko, was a South African anti-apartheid activist and ideologically an African nationalist and African socialist.

Biko was at the forefront of a grassroots anti-apartheid campaign known as the Black Consciousness Movement (BCM) during the late 1960s and 1970s.

He gained national prominence when his ideas were articulated in a series of articles published under the pseudonym ‘Frank Talk’.

Raised in a poor Xhosa family, Biko grew up in Ginsberg township in the Eastern Cape.

Biko’s given name “Bantu” means “people”. Biko interpreted this in terms of the saying “Umuntu ngumuntu ngabantu” (“a person is a person by means of other people”).Biko was raised in his family’s Anglican Christian faith and in 1950, when Biko was four, his father fell ill, and was hospitalised in St. Matthew’s Hospital, Keiskammahoek, and died, making the family dependent on his mother’s income.

Biko spent two years at St. Andrews Primary School and four at Charles Morgan Higher Primary School, both in Ginsberg.

Regarded as a particularly intelligent pupil, he was allowed to skip a year.

In 1963, he transferred to the Forbes Grant Secondary School in the township. Biko excelled at maths and English. He topped the class in his exams.

In 1964, the Ginsberg community offered him a bursary to join his brother Khaya as a student at Lovedale, a prestigious boarding school in Alice, Eastern Cape.

Within three months of Steve’s arrival, as reflected elsewhere, Khaya was accused of having connections to Poqo, the armed wing of the Pan Africanist Congress (PAC) of Azania, an African nationalist group which the government had banned in 1960 after the Sharpeville Massacre. Poqo would later convert into the Azanian People’s Liberation Army (APLA).

And in 1966, he began studying medicine at the University of Natal, where he joined the National Union of South African Students (NUSAS).

Like Black Power in the United States, South Africa’s “Black Consciousness movement” was grounded in the belief that African-descendant peoples had to overcome the enormous psychological and cultural damage imposed on them by a succession of white racist domains, such as enslavement and colonialism. Drawing upon the writings and speeches of Frantz Fanon, Aimé Césaire, and Malcolm X, advocates of Black Consciousness supported cultural and social activities that promoted a knowledge of Black protest history. They actively promoted the establishment of independent, Black-owned institutions, and favored radical reforms within school curricula that nurtured a positive Black identity for young people. — Manning Marable and Peniel Joseph.

Strongly opposed to the apartheid system of racial segregation and white-minority rule in South Africa, Biko was frustrated that NUSAS and other anti-apartheid groups were dominated by white liberals, rather than by the Blacks who were most affected by apartheid.

Biko strongly believed that well-intentioned white liberals failed to comprehend the Black experience and often acted in a paternalistic manner.

Biko developed the view that to avoid white domination, Black people had to organise independently.

To this end, Biko became a leading figure in the creation of the South African Students’ Organisation (SASO) in 1968.

Membership was open only to “Blacks”, a term that Biko used in reference not just to Bantu-speaking Africans but also to Coloureds and Indians.

Black, said Biko, is not a colour; Black is an experience. If you are oppressed, you are Black. In the South African context, this was truly revolutionary.

Biko’s subsidiary message was that the unity of the oppressed could not be achieved through clandestine armed struggle; it had to be achieved in the open, through a peaceful but militant struggle. Mamdani 2012, p. 78

Biko was careful to keep his movement independent of white liberals, but he opposed anti-white hatred and had white friends.

The white-minority National Party government were initially supportive, seeing SASO’s creation as a victory for apartheid’s ethos of racial separatism.

Influenced by the Martinican philosopher Frantz Fanon and the African-American Black Power movement, Biko and his compatriots developed Black Consciousness as SASO’s official ideology.

The BCM campaigned for an end to apartheid and the transition of South Africa toward universal suffrage and a socialist economy. It organised Black Community Programmes (BCPs) and focused on the psychological empowerment of Black people.

Biko also believed that Black people needed to rid themselves of any sense of racial inferiority, an idea he expressed by popularizing the slogan “Black is Beautiful”.

In 1972, Biko was involved in founding the Black People’s Convention (BPC) to promote Black Consciousness ideas among the wider population.

The government came to see Biko as a subversive threat and placed him under a banning order in 1973, severely restricting his activities.

Biko remained politically active though, helping to organise BCPs such as a healthcare centre and a crèche in the Ginsberg area.

During his ban he received repeated anonymous threats, and was detained by state security services on several occasions.

Both Khaya and Steve were arrested and interrogated by the police; the former was convicted, then acquitted on appeal.

Although no clear evidence of Steve’s connection to Poqo was presented, he was expelled from Lovedale.

Commenting later on this situation, he stated: “I began to develop an attitude which was much more directed at authority than at anything else. I hated authority like hell.”

From 1964 to 1965, Biko had studied at St. Francis College, a Catholic boarding school in Mariannhill, Natal.

The college had a liberal political culture, and this is where Biko developed his political consciousness.

Biko became particularly interested in the replacement of South Africa’s white minority colonial government with an administration that represented the country’s Black majority.

And among the anti-colonialist leaders who became Biko’s heroes at this time, were Algeria’s Ahmed Ben Bella and Kenya’s Jaramogi Oginga Odinga.

Biko would later say that most of the “politicos” in his family were sympathetic to the PAC, which had anti-communist and African racialist ideas.

Biko admired what he described as the PAC’s “terribly good organisation” and the courage of many of its members. But Biko remained unconvinced by its racially exclusionary approach, believing that members of all racial groups should unite against the apartheid government.

When entering the University of Natal Medical School in 1966, Biko joined what his biographer Xolela Mangcu called “a peculiarly sophisticated and cosmopolitan group of students” from across South Africa. Of which, many of them later held prominent roles in the post-apartheid era.

The late 1960s was the heyday of radical student politics across the world, as reflected in the protests of 1968, and Biko was eager to involve himself in this environment. Soon after he arrived at the university, he was elected to the Students’ Representative Council (SRC).

In July 1967, a NUSAS conference was held at Rhodes University in Grahamstown; after the students arrived, they found that dormitory accommodation had been arranged for the white and Indian delegates but not the Black Africans, who were told that they could sleep in a local church. Biko and other Black African delegates walked out of the conference in anger.

Biko later related that this event forced him to rethink his belief in the multi-racial approach to political activism: I realized that for a long time I had been holding onto this whole dogma of nonracism almost like a religion … But in the course of that debate I began to feel there was a lot lacking in the proponents of the nonracist idea … they had this problem, you know, of superiority, and they tended to take us for granted and wanted us to accept things that were second-class. They could not see why we could not consider staying in that church, and I began to feel that our understanding of our own situation in this country was not coincidental with that of these liberal whites. — Donald Woods 1978, pp. 153–154

The South African Students’ Organisation (SASO) was officially launched at a July 1969 conference at the University of the North; where the group’s constitution and basic policy platform were adopted.

SASO’s focus was on the need for contact between centres of Black student activity, including through sport, cultural activities, and debating competitions.

Though Biko played a substantial role in SASO’s creation, he sought a low public profile during its early stages, believing that this would strengthen its second level of leadership, such as his ally Barney Pityana.

Nonetheless, he was elected as SASO’s first president; Pat Matshaka was elected vice president and Wuila Mashalaba elected secretary.

Biko developed SASO’s ideology of “Black Consciousness” in conversation with other Black student leaders.

A SASO policy manifesto produced in July 1971 defined this ideology as “an attitude of mind, a way of life.”

The basic tenet of Black Consciousness is that the Blackman must reject all value systems that seek to make him a foreigner in the country of his birth and reduce his basic human dignity.

Black Consciousness centred on psychological empowerment, through combating the feelings of inferiority that most Black South Africans exhibited.

Biko believed that, as part of the struggle against apartheid and white-minority rule, Blacks should affirm their own humanity by regarding themselves as worthy of freedom and its attendant responsibilities.

SASO adopted the term over “non-white” because its leadership felt that defining themselves in opposition to white people was not a positive self-description.

Biko promoted the slogan “Black is Beautiful”, explaining that this meant “Man, you are okay as you are. Begin to look upon yourself as a human being.”

In January 1971, Biko presented a paper on “White Racism and Black Consciousness” at an academic conference in the University of Cape Town’s Abe Bailey Centre.

In 1972, the BCP hired Biko and Bokwe Mafuna, allowing Biko to continue his political and community work.

And in September 1972, Biko visited Kimberley, where he met the PAC founder and anti-apartheid activist Robert Sobukwe. Sobukwe would go on to mentor Biko.

Biko’s banning order in 1973 prevented him from working officially for the BCPs from which he had previously earned a small stipend, but he helped to set up a new BPC branch in Ginsberg, which held its first meeting in the church of a sympathetic white clergyman, David Russell.

Establishing a more permanent headquarters in Leopold Street, the branch served as a base from which to form new BCPs; these included self-help schemes such as classes in literacy, dressmaking and health education.

For Biko, community development was part of the process of infusing Black people with a sense of pride and dignity.

Near King William’s Town, a BCP Zanempilo Clinic was established to serve as a healthcare centre catering for rural Black people who would not otherwise have access to hospital facilities.

Biko also helped to revive the Ginsberg crèche, a daycare for children of working mothers, and establish a Ginsberg education fund to raise bursaries for promising local students. He helped establish Njwaxa Home Industries, a leather goods company providing jobs for local women. In 1975, he co-founded the Zimele Trust, a fund for the families of political prisoners.

“It becomes more necessary to see the truth as it is if you realise that the only vehicle for change are these people who have lost their personality. The first step therefore is to make the Blackman come to himself; to pump back life into his empty shell; to infuse him with pride and dignity, to remind him of his complicity in the crime of allowing himself to be mis-used and therefore letting evil reign supreme in the land of his birth. That is what we mean by an inward-looking process. This is the definition of Black Consciousness.” Steve Biko in, Mangcu 2014, p. 279

Biko endorsed the unification of South Africa’s Black liberationist group, among them the BCM, PAC, and African National Congress (ANC), in order to concentrate their anti-apartheid efforts. To this end, he reached out to leading members of the ANC, PAC, and Unity Movement.

Biko’s communications with the ANC were largely via Griffiths Mxenge, and plans were being made to smuggle him out of the country to meet Oliver Tambo, a leading ANC figure.

Biko’s negotiations with the PAC were primarily through intermediaries who exchanged messages between him and Sobukwe; those with the Unity Movement were largely via Fikile Bam.

In December 1975, attempting to circumvent the restrictions of the banning order, the BPC declared Biko their honorary president.

After Biko and other BCM leaders were banned, a new leadership arose, led by Muntu Myeza and Sathasivian Cooper, who were considered part of the Durban Moment.

Myeza and Cooper organised a BCM demonstration to mark Mozambique’s independence from Portuguese colonial rule in 1975.

Biko disagreed with this action, correctly predicting that the government would use it to crack down on the BCM.

The government arrested around 200 BCM activists, nine of whom were brought before the Supreme Court, accused of subversion by intent. The state claimed that Black Consciousness philosophy was likely to cause “racial confrontation” and therefore threatened public safety. Biko was called as a witness for the defense; he sought to refute the state’s accusations by outlining the movement’s aims and development.

Ultimately, the accused were convicted and imprisoned on Robben Island.

The state security services repeatedly sought to intimidate Biko; he received anonymous threatening phone calls,and gun shots were fired at his house.

A group of young men calling themselves ‘The Cubans’ began guarding him from these attacks.The security services detained him four times, once for 101 days. With the ban preventing him from gaining employment, the strained economic situation impacted his marriage.

During his ban, Biko asked for a meeting with Donald Woods, the white liberal editor of the Daily Dispatch. Under Woods’ editorship, the newspaper had published articles criticising apartheid and the white-minority regime and had also given space to the views of various Black groups, but not the BCM. Biko hoped to convince Woods to give the movement greater coverage and an outlet for its views. Woods was initially reticent, believing that Biko and the BCM advocated “for racial exclusivism in reverse”. When he met Biko for the first time, Woods expressed his concern about the anti-white liberal sentiment of Biko’s early writings. Biko acknowledged that his earlier “antiliberal” writings were “overkill”, but said that he remained committed to the basic message contained within them.

Over the coming years the pair became close friends.Woods later related that, although he continued to have concerns about “the unavoidably racist aspects of Black Consciousness”, it was “both a revelation and education” to socialise with Blacks who had “psychologically emancipated attitudes”. Biko also remained friends with another prominent white liberal, Duncan Innes, who served as NUSAS President in 1969; Innes later commented that Biko was “invaluable in helping me to understand Black oppression, not only socially and politically, but also psychologically and intellectually”. Biko’s friendship with these white liberals came under criticism from some members of the BCM.

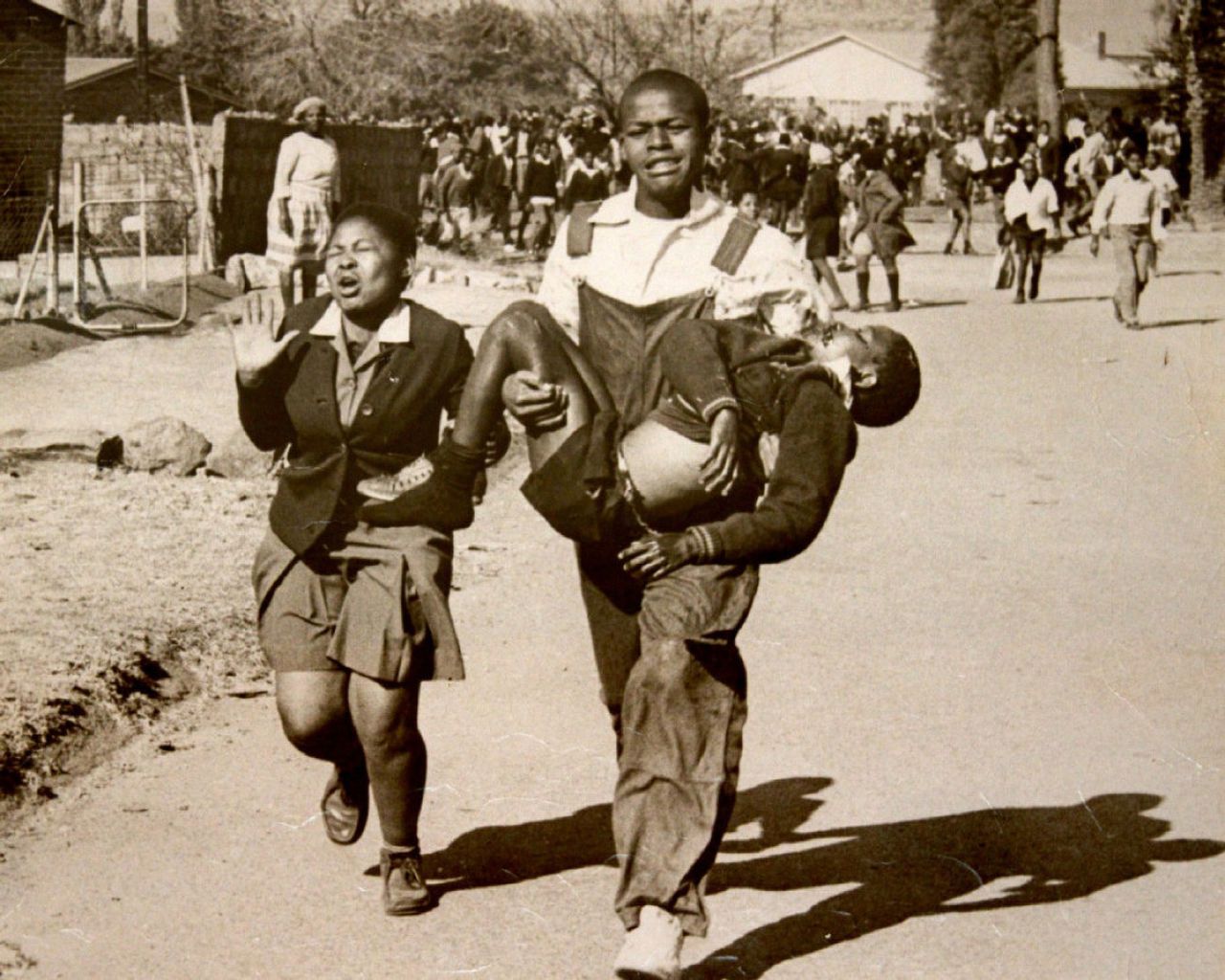

Following his arrest in August 1977, Biko was beaten to death by state security officers.

The security services took Biko to the Walmer police station in Port Elizabeth, where he was held naked in a cell with his legs in shackles.

On September 6, he was transferred from Walmer to room 619 of the security police headquarters in the Sanlam Building in central Port Elizabeth, where he was interrogated for 22 hours, handcuffed and in shackles, and chained to a grille.

Exactly what happened has never been ascertained, but during the interrogation he was severely beaten by at least one of the ten security police officers.

He suffered three brain lesions that resulted in a massive brain haemorrhage on September 6.

Following this incident, Biko’s captors forced him to remain standing and shackled to the wall.

The police later said that Biko had attacked one of them with a chair, forcing them to subdue him and place him in handcuffs and leg irons.

Biko was examined by a doctor, Ivor Lang, who stated that there was no evidence of injury on Biko. Later scholarship has suggested Biko’s injuries must have been obvious.

He was then examined by two other doctors who, after a test showed blood cells to have entered Biko’s spinal fluid, agreed that he should be transported to a prison hospital in Pretoria.

On September 11, police loaded him into the back of a Land Rover, naked and manacled, and drove him 740 miles (1,190 km) to the hospital.

There, Biko died alone in a cell on September 12, 1977.

According to an autopsy, an “extensive brain injury” had caused “centralisation of the blood circulation to such an extent that there had been intravasal blood coagulation, acute kidney failure, and uremia”.

He was the twenty-first person to die in a South African prison in twelve months, and the forty-sixth political detainee to die during interrogation since the government introduced laws permitting imprisonment without trial in 1963.

News of Biko’s death spread quickly across the world, and became symbolic of the abuses of the apartheid system.

His death attracted more global attention than he had ever attained during his lifetime.

Protest meetings were held in several cities; many were shocked that the security authorities would kill such a prominent dissident leader.

Biko’s Anglican funeral service, held on September 25, 1977 at King William’s Town’s Victoria Stadium, took five hours and was attended by over 20,000 people.

The vast majority were Black, but a few hundred whites also attended, including Biko’s friends, such as Russell and Woods, and prominent progressive figures like Helen Suzman, Alex Boraine, and Zach de Beer.

Foreign diplomats from thirteen nations were present, as was an Anglican delegation headed by Bishop Desmond Tutu.

The event was later described as “the first mass political funeral in the country”.

Biko’s coffin had been decorated with the motifs of a clenched Black fist, the African continent, and the statement “One Azania, One Nation”; Azania was the name that many activists wanted South Africa to adopt post-apartheid.

Biko was buried in the cemetery at Ginsberg. Two BCM-affiliated artists, Dikobé Ben Martins and Robin Holmes, produced a T-shirt marking the event; the design was banned the following year.

Martins also created a commemorative poster for the funeral, the first in a tradition of funeral posters that proved popular throughout the 1980s. Biko’s fame spread posthumously.

Furthermore, Biko became the subject of numerous songs and works of art, while a 1978 biography by his friend Donald Woods formed the basis for the 1987 film, Cry Freedom.

During Steve Biko’s life, the government alleged that he hated whites, various anti-apartheid activists accused him of sexism, and African racial nationalists criticised his united front with Coloureds and Indians.

Nonetheless, Biko became one of the earliest icons of the movement against apartheid, and is regarded as a political martyr and the “Godfather of Black Consciousness”.

Black Consciousness directs itself to the Blackman and to his situation, and the Blackman is subjected to two forces in this country. He is first of all oppressed by an external world through institutionalised machinery and through laws that restrict him from doing certain things, through heavy work conditions, through poor pay, through difficult living conditions, through poor education, these are all external to him. Secondly, and this we regard as the most important, the Blackman in himself has developed a certain state of alienation, he rejects himself precisely because he attaches the meaning white to all that is good, in other words he equates good with white. This arises out of his living and it arises out of his development from childhood. Steve Biko in, Woods 1978, p. 124